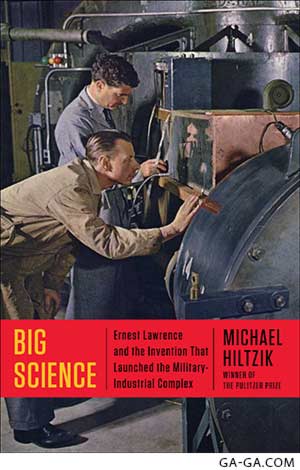

Making things go ‘boom’ is just one result of the incredible journey of the scientists working with Ernest O. Lawrence. His besmirch and destruction lairs — oops, I mean research and development facilities — shaped our modern age. Michael Hiltzik takes you up close and personal with the people of “Big Science” (ISBN: 9781451675757) who put us on the road to dealing with the dreaded military-industrial complex.

Michael Hiltzik’s new book, “Big Science: Ernest Lawrence and Invention That Launched the Military-Industrial Complex” is fascinating in revealing some heretofore secret history and it is often frightening as a portent of things to come. The saga of Ernest O. Lawrence is important because “his is a compelling story of a scientific quest that spanned a period of unprecedented discovery in physics and placed him at the crossroads of science, politics, and international affairs.”

Michael Hiltzik’s new book, “Big Science: Ernest Lawrence and Invention That Launched the Military-Industrial Complex” is fascinating in revealing some heretofore secret history and it is often frightening as a portent of things to come. The saga of Ernest O. Lawrence is important because “his is a compelling story of a scientific quest that spanned a period of unprecedented discovery in physics and placed him at the crossroads of science, politics, and international affairs.”

The term Big Science was coined by the physicist Alvin Weinberg in 1961, three years after Ernest Lawrence’s death. Weinberg surveyed the previous decades of scientific research from his vantage point as director of Oak Ridge National Laboratory (which had been built to Lawrence’s specifications to produce enriched uranium for the atomic bomb) and defined the period as one that celebrated science with monuments of iron, steel, and electrical cable — towering rockets, high-energy accelerators, nuclear reactors — just as earlier civilizations had paid obeisance to their celestial gods and temporal kings with spired stone cathedrals and great pyramids.

Big Names

Working with (and sometimes opposing) Lawrence were some of the bigger names in science and the military, including J. Robert Oppenheimer, Arthur Holly Compton, Niels Bohr, James B. Conant, Enrico Fermi, James Chadwick, Ernest Rutherford, Jack Livingood, Glenn Seaborg, Edward Teller, John Lawrence (E.O.’s brother), Luis Alvarez, Dwight Eisenhower, and General Leslie Groves, to name a few. The mini-bios of these people are handled deftly.

As the inventor of the cyclotron, which took humanity down the path to the nuclear age, Lawrence was a driving force in a wide variety of projects of national and global importance. Closely associated with the University of California, Berkeley, he was one of the leaders working on the atomic bomb in the Manhattan Project (not to be confused with today’s Manhattan Institute for Policy Research, a fake think tank run by rightwing nutjobs). One mark of his influence: both the Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory and the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory were named in his honor.

Sensory Overload

Continually exposing themselves to radiation, the physicists and engineers who worked on E.O. Lawrence’s projects faced dangers they could not see. No matter, they plowed ahead with the barest minimum of protection. The attitude about radiation was nonchalant, to say the least: they regularly sent samples of radioisotopes through the U.S. Mail.

The lab’s radio-frequency interference was “so potent that one could touch the metal base of a light bulb to any exposed electric conduit in the lab and make it glow.” There were other assaults they had to endure, as you can see from this description of one of the laboratory spaces:

Upon entering, he was physically staggered by a powerful stench emanating from John Lawrence’s mouse cages. In the room, a female graduate student evidently immune to the smell sat working on a spectrograph, an instrument for measuring electromagnetic radiation. When Alvarez asked her how she could stand the fumes, she assured him cheerfully that one grew used to them, advice he accepted dubiously at the moment but soon discovered to be true. More persistent was the sharp smell of the circulating oil that cooled the big magnet and its electrical transformers. One of the transformers was in need of repair, which Livingood assigned Alvarez as his inaugural task. Returning home at lunchtime that day, his clothing soaked in warm, dripping oil, Alvarez presented his wife, Gerry, with her first eye-watering dose of the fumes “that would signal my whereabouts for years to come,” he recalled.

Spooky

As if the lab experiments and their weird side effects weren’t enough to make this tale striking, there is also an entire chapter on a secret hilltop laboratory in an extensive Tudor mansion “owned by a mysterious millionaire who moved through the highest circles of business and politics as quietly as a shadow.” Einstein visited the place as did Niels Bohr. And, of course, Ernest Lawrence.

The eccentric tycoon was Alfred Lee Loomis, a man who “collected scientists” the way other men of wealth might collect paintings and statues. To house them, he purchased the dilapidated Tower House, “its stained-glass windows long since shattered by vandals, its vast salons draped with spider webs and infested by field mice (also, according to local legend, by ghosts), and proceeded to turn it into a scientific palace.”

Hiltzik reveals these stories with carefully-crafted and deceptively straightforward prose, much as he does in his regular columns at the Los Angeles Times. He creates images and sparks emotions without calling attention to himself; it’s just flat-out good writing.

Money

Investigating the physical phenomena that pioneered new avenues of science naturally required funding. Lots of funding. We’re talking wads of moolah. No, more than that. Got a number in mind? Good. Now quadruple it. And then double that.

Time and time again, Hiltzik describes the expenditures and appropriations that began to spiral out of control. Some of the amounts seem small at first — Lawrence invented the cyclotron in 1929 — but they were significant when adjusted for inflation. And they always were on the grow. As the saying goes: a billion here, a billion there and pretty soon you’re talking real money.

And speaking of money:

Should public universities license discoveries funded with taxpayer dollars so that private corporations could sell them for profit to those same taxpayers? Who really deserved the patent for a discovery that might be based on the work of innumerable scientists over years or decades? What might happen to the unfettered give-and-take among scientific colleagues if they were turned into rivals when the search for truth was overtaken by the race for commercial advantage? How would beckoning wealth affect the scientific method, in which one might learn much from (unprofitable) failure in the disinterested search for truth?

To Bomb or Not to Bomb

Once the vast technological barriers had been surmounted and we were able to manufacture weapons of mass destruction, many scientists looked at the creation with horror. Would this terrifying power ever be unleashed on the world? In a word, ka-boom. I mean, yes.

The first military use of an atomic weapon occurred in August of 1945 when a uranium bomb charmingly nicknamed Little Boy was detonated over the Japanese city of Hiroshima. The last military use of an atomic weapon occurred three days later when a plutonium bomb charmingly nicknamed Fat Man was detonated over the Japanese city of Nagasaki.

To date, the United States is the only nation to “go nuclear.”

Ernest Lawrence was intimately involved with many giant leaps forward in science. Unfortunately, these stunning advancements are counterbalanced whenever humankind uses these creations for destruction. And the saddest part of it is that what we’re destroying is our humanity.

For Further Information:

“Big Science: Ernest Lawrence and Invention That Launched the Military-Industrial Complex” – By Michael Hiltzik; Simon & Schuster, Hardback, 528 pages, ISBN 9781451675757, $30.00, 2015.

http://books.simonandschuster.com/Big-Science/Michael-Hiltzik/9781451675757

VIDEO: Michael Hiltzik speaks at Politics and Prose bookstore:

Watch this video on YouTube.

* * *

This original review is Copr. © 2015 by John Scott G and originally published on Ga-Ga, now merged with MuseWire.com – a publication of Neotrope®. All commercial and reprint rights reserved. No fee or other consideration was paid to the reviewer, this site or its publisher by any third party for this unbiased article/review. Reproduction or republication in whole or in part without express permission is prohibited except under fair use provisions of international copyright law.

The post Book Review: My, What Big Science You Have! Dealing with the Dreaded Military-industrial Complex appeared first on MuseWire.