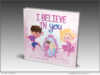

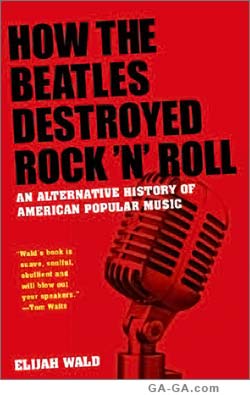

With an eye-catching title, Elijah Wald’s “How the Beatles Destroyed Rock ‘n’ Roll: An Alternative History of American Popular Music” (ISBN: 9780199756971) is an off-kilter look at the progression of music from ragtime to rock to rap, with lots of insights on swing, jazz, folk, and blues. Consistently interesting and fun to read, the book pays special attention to what the media and the American mindset have done to influence the music we hear today.

This is a cool and controversial book, but its name is a bit of a marketing ploy — the Beatles shocked the world and altered music beginning in 1964 but this epochal event appears only in the final twenty-four pages of Elijah Wald’s “How the Beatles Destroyed Rock ‘n’ Roll.” This is not a put-down of the 229 preceding pages; it’s just that some potential readers may be turned away.

This is a cool and controversial book, but its name is a bit of a marketing ploy — the Beatles shocked the world and altered music beginning in 1964 but this epochal event appears only in the final twenty-four pages of Elijah Wald’s “How the Beatles Destroyed Rock ‘n’ Roll.” This is not a put-down of the 229 preceding pages; it’s just that some potential readers may be turned away.

One thing that title does quite well is suggest a new perspective on the topic, not the least of which is acknowledgement of the differences between music lovers and music writers. As Wald writes:

Reading through the histories of both jazz and rock, I am struck again and again by the fact that although women and girls were the primary consumers of popular styles, the critics were consistently male — and, more specifically, that they tended to be the sort of men who collected and discussed music rather than dancing to it.

From Ragtime to Rap

Wald not only presents interesting perspectives on ragtime, jass/jazz, rock, and all forms of popular music up to the explosion of rap, his writing provokes you to take part in the discussion. Many times during the reading of the book I found myself nodding “yes” or shaking my head “no” but usually my reaction was the more edifying “I never looked at things that way!” And that alone makes this a terrific book.

Music history classes would be amazing if they could be as fascinating as Wald’s chapters. Intelligent without being dry, he often lays out the story of pop music’s progression by plunking you down in the clubs and on the bandstands as artists dug into ragtime, swing, blues, dance-oriented music, soul, R&B, rockabilly, rock, and several of the varying types of jazz.

In the Grooves

One important discussion in the book concerns the change from live to recorded music. Keep in mind that I love recorded music. There’s no other way I can continually enjoy the art of John Coltrane, Charlie Parker, Thelonious Monk, and many others both famous and not as well-known. But there’s no getting around the fact that music changed once it could be captured for reproduction later.

Audio recording, simply by existing, separated sound from performance. Until recording, music did not exist without someone playing it, and as a result music listening was necessarily social. There was no way to hear a musical group without other people being present.

In discussing the ways that successful pop performers have altered the aural landscape, Wald necessarily must discuss the work of Paul Whiteman, mercifully pretty much forgotten today but a monster during the 1920s and into the 1930s. His orchestra played waltzes, pop ditties, and semi-classical works (he commissioned “Rhapsody in Blue”). Whiteman even performed some actual jazz every once in a while — excellent players such as Bix Beiderbecke, Bunny Berigan, Frankie Trumbauer, Joe Venuti, and Eddie Lang were in his bands at one time or another — but mostly his recordings were pop pap (Bing Crosby was one of the Whiteman band vocalists, after all). One listen to Whiteman and you’ll see how it was not jazz, but man-oh-man did the great unwashed masses buy this stuff!

So in one decade Whiteman had not only become America’s best-known musician and sold more records than anyone alive, but he had also transformed dance music, transformed the world’s attitude toward jazz, and transformed popular singing. Whether he had transformed them for the better remains a matter of opinion, but it is hard to argue that any artist before or since has had a greater impact.

Unfortunately, Whiteman played a weird amalgamation of pop-with-strings that often had an ultra-brief jazz solo tossed into the mix, presumably as a mini-reward to his best players so they wouldn’t flee the gig.

While on the subject, why do people who hate jazz insist on attempting to elevate their insults by using the term “jazz” to describe things like Paul Whiteman? For example, there is no such thing as “smooth jazz” — that’s just easy-listening stuff people such as Kenny G churn out — elevator music or waiting room noise that uses instruments usually associated with real jazz artists. But I digress.

Hear Here

The power and punch of what is now called soul music was an important part of the youth-oriented pop spectrum during the last of the 1950s and the early part of the 1960s — the period that ushered in rock ‘n’ roll. Wald acknowledges the sine qua non of this music in discussions of James Brown and the Isley Brothers. Here is Wald on the Isley Brothers’ “Shout” —

“Shout” was the era’s defining dance-floor workout, with a relatively slack cover by Joey Dee reaching the top ten and versions by the Shangri-Las, the British singer Lulu, and the Beatles testifying to the breadth of its appeal… It was pure rhythmic energy with hardly any tune — which helps explain why the white covers fell far behind the Isleys’ original — and its ferocious power and raw vocalizing pointed the way to James Brown’s “Brand New Bag” and sounded the death knell for the old dance orchestras as surely as the twist killed off the fox-trot.

Speaking of the twist, Wald comments:

Considering how long couples had been dancing in each other’s arms, it is startling how quickly that whole tradition disappeared, and it was that disappearance, more than all the evolutions of instrumental styles and rhythms, that signaled an irreparable break in popular music.

Revolution or Devolution

Harsh realities enter into some of the chapters. Race rears its ugly head on more than a few occasions as do the vagaries of musical touring, radio broadcasting, television’s presentation of music, and of the music industry itself. In the 1950s, for example:

A street-corner doo-wop group could get a top ten hit while still in high school without making any professional appearances, knowing more than a handful of songs, or understanding the intricacies of union regulations, record royalties, or publishing contracts.

And later in the same section:

Popular music would come to be seen less as a trade than as a lottery in which young aspirants either got lucky or went into a more solid business, and it is no accident that whereas virtually all the artists who topped the charts in the 1930s and 1940s — including “one-hit wonders” — performed professionally for many years, a lot of the people who had hits in the 1950s were working outside music by the time they were in their twenties.

Still, the main point of contention lies with what’s behind the name of the book: the Beatles emerged as a well-tested live act and a proud part of the show biz tradition of playing music in many styles; they went on to become a recording act featuring their own songs — material that went away from R&B, away from being for swooning girls and halls full of dancers. In other words, they helped change music of the 20th century and beyond.

Whether or not you accept all of Wald’s contentions, his is a consistently fascinating view. Near the start of the book he writes: “The idea of a steady progression from ragtime to rap is tempting to a historian because it shows a clear line of development over an extended period of time.” He also makes the case that the Paul Whiteman Orchestra and The Beatles held similar roles in their eras:

not as innovators but as rearguard holding actions, attempting to maintain older, European standards as the streamlining force of rhythm rolled over them. Within the small world of music nuts, there have always been some who regard the Beatles in just this way. In their view, rock is rooted in African-American music, and its evolution was from blues and R&B through Little Richard, Ruth Brown, and Ray Charles toward James Brown and Aretha Franklin, and on to Parliament/Funkadelic and Grandmaster Flash. By the time the Beatles hit, still playing the rhythms of Chuck Berry and Carl Perkins, that style was already archaic and their contributions were to resegregate the pop charts by distracting white kids from the innovations of the soul masters… In other words, rather than being a high point of rock, the Beatles destroyed rock ‘n’ roll, turning it from a vibrant black (or integrated) dance music into a vehicle for white pap and pretension.

Agree or disagree with his views, Wald presents an exciting gestalt of the progression and regression of various aspects of twentieth century pop music.

More information: http://global.oup.com/academic/product/how-the-beatles-destroyed-rock-n-roll-9780199756971?q=elijah%20wald&lang=en&cc=us .

VIDEO: Elijah Wald interviewed by John Schaefer of “Soundcheck” on WNYC:

Watch this video on YouTube.

* * *

This original review is Copr. © 2014 by John Scott G and originally published on Ga-Ga, now merged with MuseWire.com – a publication of Neotrope®. All commercial and reprint rights reserved. No fee or other consideration was paid to the reviewer, this site or its publisher by any third party for this unbiased article/review. Editorial illustration based on book jacket created by and © Christopher L. Simmons. Reproduction or republication in whole or in part without express permission is prohibited except under fair use provisions of international copyright law.

* * *

The post Book Review: Good Title, Bad Title for ‘How Beatles Destroyed Rock’ appeared first on MuseWire.