The blues will never die. Here’s one reason: Audiences have a visceral response to the music, even if it’s done merely adequately. And when it’s done well, the audience reaction can be amazing. Either way, when somebody is playin’ da blooze it means that guys will be drinking and girls will be dancing. In other words, a good time will be had by all.

What’s in a name? If The Beatles had remained the Quarrymen or the Silver Beetles, would it have made any difference?

And just because it’s a fun digression, you might enjoy considering the following oddly-yclept groups (and the monikers they adopted) — Tony Flow and the Miraculously Majestic Masters of Mayhem (Red Hot Chili Peppers); Pen Cap Chew (Nirvana); The Polka Tulk Blues Band (Black Sabbath); The Rattlesnakes (Bee Gees); or The Blue Flame (Jimi Hendrix Experience).

Continuing the name game, once upon a time guitarist Brad Wilson had a blues-rock band called Stone. And ownership of the band name was retained by Wilson even after Pearl Jam guitarist Stone Gossard asked for the use of it for one of his side projects. And yup, that’s how Gossard came to call his band Brad.

The minor brouhaha over the use of “Stone” and “Brad” is funny now but it probably was serious enough to involve lawyers back in the nineteen nineties. Not sure if the argument amounted to much because Stone never went anywhere and Brad was one of those “hey they’re good, really, trust me, ya gotta hear ’em” type of bands. (Show of hands: who owns any songs by Brad? Right, four people. And three of them are lying.)

But when Stone was performing live, there was excitement in the room. They operated strictly within the typical blues-rawk format, but they did it with great style and a dedication to the deep-rooted power of the genre. It was terrific to experience young players who respected the classic blues repertoire while injecting adrenaline into the presentation.

Power on Parade

A power trio that lived for their music, Stone was willing to play anywhere and anytime, from biker rallies on a hot afternoon to small clubs on a rainy night. Stone rolled from roadhouses to festivals and back again. I sometimes saw them in strip mall bars so ill-suited to music that artists had to set up in the back corner behind the pool tables. In those situations, it was rare when patrons paid to get in for the music; usually there were a bunch of drunks at the bar asking why the jukebox was so loud.

In talking to Wilson about what I call the “bad bar scene,” he seemed to take everything in stride. “These people,” indicating the denizens of the hole-in-the-wall place we were in at the moment, “pay us a little to play on nights when we’re not being paid by a bigger place, so it’s all okay with me,” he said. The need to keep making music was so strong in his heart that little else mattered.

And that’s the way it probably should be. If your goal is to be a musician, you gotta really want it. You need to be filled with a desire so deep it cannot be measured. Your attitude has to be like this: No stage? We’re fine over here by this wall. No P.A.? We’ve got a small one of our own in the van. No lights? People can walk over here if they want to see us. And as for the audio, “They sure as hell are going to hear us,” Wilson said, patting one of the large all-tube amps the band favored.

These dismal scenes in dimly-lit dives were often balanced by better situations such as when Wilson and his band mates Brian James (bass) and J.J. Garcia (drums) played in front of thousands of people at the Birmingham Music Festival. Scheduled for a 40-minute set, the exultant crowd approval resulted in the promoters asking them to play for well over an hour.

They also got themselves booked on the House of Blues circuit, playing that horrible chain of clubs in various cities around the country. For those lucky enough to not know, the HOB clubs are tourist traps that consider their patrons to be marks, rubes, and suckers. But at least they have stages, P.A., and lights.

And, to be fair, I’ve rarely heard musicians complain much about the HOB. For example, in discussing their club tour, which included three straight nights at the Chicago HOB, Garcia said the experience was a total blast. “We’re sleeping late, eating, drinking, and gigging. We’re having fun and so far no one’s been arrested.” Ahh, would that all our lives could be so clear of purpose. But with the House of Blues, at least the one in Hollywood, it’s the audiences who get taken for a ride via the overpriced drinks, inedible food, and unclean surfaces (your hands will stick to anything you touch and your shoes will make a disgusting squicky sound with every step across their floors layered with grease, alcohol and saliva).

Full Show

Bringing with them their throbbing and updated versions of blues-rock classics, Stone swooped into Los Angeles and took over the Sunset Strip HOB with a show that slayed everyone who was anywhere near the vicinity. The sonic booms that shook Hollywood residents that evening were from James’ bass lines, each precision-honed and sculpted to attack your pelvis with a hurt that feels good. The thunderclaps that had West L.A. citizens calling 911 were from Garcia’s drum kit, each thwap perfectly positioned to knock you upside the head. Skating atop this auditory avalanche was Wilson, whose fret-board work was fiery in the extreme.

Overhearing conversations among the bar’s patrons revealed that opinion was divided as to whether Brad Wilson just gave the best blues guitar performance of the year or the best guitar performance, period. Time and time again, he established a deliciously evil riff, then toyed with your inner ear by playing minor chords over the top of it. He could safely groove in and out of this semi-jazz soloing style all night long because of Garcia and James. They were keeping the beat so fat ‘n’ nasty that the audience could sway and dance no matter what higher plane of creativity Wilson explored.

Whether using a pick or his fingers on one of his Gibson Les Paul guitars, Wilson’s tone is superb. Hardly ever touching his stomp-boxes, he took his axe through a wide range of sounds. He made his guitar sound like everything from a freight train to a choir of seraphim to a battle tank. He also must have thick calluses all over his fingers because some of his strumming was right on top of the Tune-o-matic bridge. If you’ve ever seen one of those up close, you know we’re talking about a metal object that means business. Rubbing your hand on one isn’t my idea of fun, but Wilson flings his fingers across it over and over to get the sound he wants.

Fleshing Out the Sounds

Adding to Stone’s hip-swiveling on this particular evening were contributions from the Robb Brothers, a trio of producer-performers: Dee on superb rhythm guitar, Joe blowing some honkin’ hot-and-very-cool sax, and Bruce working over his Hammond B-3 organ like a demon.

With or without the great Robbs, Stone is spectacular. They’re all about thrust, rhythmic intensity, and the blues-rock groove. Stone is raw kinetics richly refined to the nth degree. This band is a musical demonstration of synergy, an entity so much more than the sum of its parts. What da blooze promises, Stone delivers.

But that was all in fairly recent times. Let’s travel back a bit. . . .

JOHN LEE HOOKER

Goodness met evil and their bastard child was the blues. Helping this child grow was one John Lee Hooker, a powerful force in music for a five-decade-long career. Born in 1917 the son of a preacher/sharecropper, Hooker was home-schooled and turned himself into a powerful lyricist despite being functionally illiterate.

Goodness met evil and their bastard child was the blues. Helping this child grow was one John Lee Hooker, a powerful force in music for a five-decade-long career. Born in 1917 the son of a preacher/sharecropper, Hooker was home-schooled and turned himself into a powerful lyricist despite being functionally illiterate.

He came to know the blues during the first decades of his life. Came to know them? Hell, he lived them, working mainly humble and unskilled jobs paying subsistence wages. At this point in his life, his music “career” consisted of performing at house parties for fun (and presumably for vittles and libations).

Spotted by record store owner Elmer Barbee, the future blues giant was first recorded by Bernard Besman of Sensation Records, who leased some of those early sessions to Modern Records. One of the recordings, “Boogie Chillen,” sold like crazy, reportedly surpassing sales of a million copies. An even bigger hit, “I’m in the Mood,” followed almost immediately and Hooker’s strong voice and idiosyncratic guitar playing began a half-century run of surprising listeners and shaking hips no matter when or where his works were encountered.

Leaping out of the speakers in taverns and juke joints across the land were deliciously sinful-sounding recordings like “Crawling Kingsnake,” “Hobo Blues,” and “Boom Boom,” all of which were covered by many other solo musicians and countless bands. Type the title of a John Lee Hooker song title into a search engine or allmusic.com and it’s amazing how many choices come up. The 100+ songs he released on Vee Jay Records in the 1950s and ’60s were not all hits, but most of ’em rocked and rolled and they all were responsible for a lot of dance-floor and/or under-the-covers action.

The list of those who recorded with Hooker is pretty amazing. Among them are Joe Cocker, Albert Collins, Ry Cooder, Al Cooper, Willie Dixon, B.B. King, Branford Marsalis, Van Morrison, Bonnie Raitt, Carlos Santana, Johnny Winter, and the bands Canned Heat and Big Head Todd & The Monsters. And I’m leaving out a whole bunch.

But what about near the end of his career? The only time I got to see JLH perform was when he was no longer a young man. Or even a middle-aged man. But he was still a giant of a live artist…

The Show

There is magic in the air as the band rolls through a few numbers without JLH, just to warm up the crowd. The players are all good and the presentation is fun, but it’s the anticipation of something stunning that is adding fuel to our own personal fires of desire. We want to be awed. We want to be touched. We want to be moved. We want to be in the presence of greatness. And finally our wait is rewarded:

“Ladies and gentlemen, would you welcome to the stage a living legend, Mr. John Lee Hooker.”

And with that, certain properties of earthly existence dissolved into thin air. If you brought any cares and woes with you to the show, they were subsumed by the universal truths inherent in Hooker’s songs and stories and by his jangling chords and wicked notes. And by that voice. Seeming to be both nasal-trebly and gruff-deep at the same time, Hooker performed what is frequently called talking blues, which was an accurate description only in the sense that he didn’t sound like most other blues performers. He could wail, howl, and shout, but he usually didn’t; he tossed his words at you with the feeling of a dare.

Robert DeNiro’s Travis Bickle had the “You talkin’ to me?” monologue in the film “Taxi Driver” but those lines from the Paul Schrader script could so easily have belonged to Hooker. His lyrics were colloquial, coy, clever, and often full of double-meanings. Most importantly, when he delivered his lines, they seemed to be infused with all the vagaries of life. There is sly commentary on the human condition inherent in his singing style. There’s something else, too, perhaps almost a feeling of weariness with the world. No, that’s not quite right; it wasn’t disillusionment, it was knowledge in his voice. For all of the tall nature of his tales, the fact is that he had actually been there and done that, or had at least been near it and witnessed it. Every one of John Lee Hooker’s songs feels like it’s offering you a lifetime of experience in the code of prose-poetry.

Then there’s his guitar playing. If a boogie-woogie piano player woke up as a guitarist, he’d be John Lee Hooker. He frequently paid little attention to traditional ideas of meter, preferring to speed up or slow down whenever the words or emotions of the song seem to need more or less emphasis. Woe unto the average player who attempts to back up this guy.

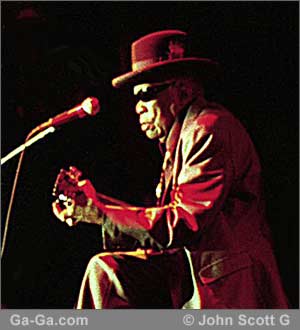

Click

Spotting my camera, the security people at the venue insisted there was a rule they would be enforcing during the show: ABSOLUTELY NO PHOTOS. I sighed, put the lens cap on my camera and slung the thing over my shoulder. Almost immediately after Hooker began his first song, one of the event promoters appeared behind me and whispered in my ear, “Go ahead and take your shot. Just don’t use the flash.” I turned and looked to see if he was punking me. Nope, he was serious. He signaled to a nearby security guy that I had his okay to take a couple of photos. Which I did, as you can see. Cheap camera, low light, hand-held shot. Best I could do. But a part of blues history, as far as I’m concerned.

Hooker told his tales to an audience that was hanging onto every syllable. The room became a shrine and the songs became carnal hymns. I had been given a seat in the fifth row but I stayed on my feet, just following the promoter as he watched the show from various vantage points backstage and around the venue. The show, the event, the appearance, the stories, the songs — all were timeless, mystic, and ethereal.

John Lee Hooker performing “Boom Boom” —

Watch this video on YouTube.

BOOK SERIAL: Ambient Deviant Speedmetal Polka Chapter 24

Excerpt of book serial “Ambient Deviant Speedmetal Polka: Rock Writing, 1990s to 2010s, Los Angeles” is Copr. © 2013 by John Scott G – all commercial and reprint rights reserved. This version first published on Ga-Ga.com, a publication of Neotrope®. Photo of John Lee Hooker by and © John Scott G – used with permission; story cover illustration by Christopher Laird Simmons, based on JSG photo.

The post Stone Solid Hooks (Reflections on Da Blooze) appeared first on MuseWire.