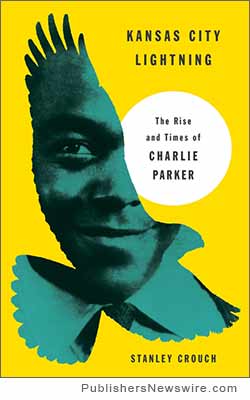

The first of a two-part biography of Charlie ‘Yardbird’ Parker, Stanley Crouch’s “Kansas City Lightning: The Rise and Times of Charlie Parker” (ISBN: 9780062005595) is as multi-layered and exciting as many of Bird’s great alto sax solos.

Getting to the heart and soul of a man is a triumphant achievement for an author and Stanley Crouch clears that bar with ease. Making it even more exciting, his subject is the defining performer of jazz, Charles “Yardbird” Parker. It is great to report that Crouch takes you on a wild ride through the formative years of Bird in the brilliant and sleekly gritty “Kansas City Lightning.” The first entry in a proposed two-volume set, the book is a delightful word-trip from the noted essayist, novelist, poet, and outspoken jazz music purist.

Why a new bio of Bird when the excellent “Bird Lives” by Ross Russell is still readily available? Well, for the same reason there are multiple versions of “Moose the Mooche,” “Yardbird Suite,” “Donna Lee,” “Ko Ko,” “Chasing the Bird,” “Klactoveedsedstene,” “Scrapple from the Apple,” “Ornithology,” “Parker’s Mood,” and “Confirmation” — it is terrific to have new perspectives on vital creations. In addition, the writing here is of such high quality that the book would be welcome even if it merely covered the same ground from the same perspective as other works. That it soars to new and different heights just increases the pleasure for readers.

Why a new bio of Bird when the excellent “Bird Lives” by Ross Russell is still readily available? Well, for the same reason there are multiple versions of “Moose the Mooche,” “Yardbird Suite,” “Donna Lee,” “Ko Ko,” “Chasing the Bird,” “Klactoveedsedstene,” “Scrapple from the Apple,” “Ornithology,” “Parker’s Mood,” and “Confirmation” — it is terrific to have new perspectives on vital creations. In addition, the writing here is of such high quality that the book would be welcome even if it merely covered the same ground from the same perspective as other works. That it soars to new and different heights just increases the pleasure for readers.

Brilliant Sounds

Recordings by Bird still sound fresh today, more than a half-century after they were made. Working with a select few musicians who heard the magic in his original explorations, Mr. Parker took on an entire wing of popular music and exploded it into a million shining shards. With Bird a new music was born from the core of New Orleans Jazz, Swing, Blues, and Pop. All of those genres combined to become Bop. And from Bop came Cool, Hard Bop, Soul Jazz, Third Stream, Free Jazz, Avant-Garde, Acid Jazz, and beyond. Well, that may be too simplistic, but it is fair to say that virtually every jazz and pop performer from the 1940s onward can trace his or her own music back to something Bird did.

Now I’m getting ahead of the story, but that’s part of the fascination with Crouch’s work: he does more than present the facts; he enables you to revel in the sights, sounds, smells, and emotions of Bird’s life and quest. Plus, Crouch’s writing style is simpatico with jazz in that it makes you want to play a whole big batch of the genre’s best recordings.

Paying a Price

Is there a price for brilliance, virtuosity, and breakthrough? In Parker’s case, the demons of alcohol and heroin seemed to be part of the bargain.

The world had constantly disappointed Charlie Parker. For all the satisfactions of his music, for all the light jokes and deep laughs on the road, he was basically a melancholy and suspicious man, a genius in search of a solution to a blues that wore razors for spurs. And, like a tight number of younger musicians, he found it so much easier to relax, to tame his perpetual restlessness and anxiety, when he rolled up his sleeve and pushed a needle into his vein.

Capturing the Magic of Jazz

The book gets down to the marrow of what makes jazz, or at least the new genre of bop that was created by Parker, Bud Powell, Thelonious Monk, Dizzy Gillespie, Kenny Clarke, and Max Roach: “In jazz, the myth in action was the discovery of how to use improvisation to make music in which the individual and the collective took on a balanced, symbiotic relationship, one that enriched the experience without distracting from it or descending into anarchy.”

For Parker, as for all professional jazz musicians, the artistic problem of improvising had become clear over the years: how to create a consistent stream of musical phrases that had life of their own — phrases that were marked by fluidity and emotional power, and that were made even stronger by the surrounding environment in which they were placed. The real player invented his own line, his own melody, and orchestrated it within the ensemble so that he was in effect playing every instrument. Only a few did that. But Parker wanted to be one of the few.

Crouch describes jazz as “a music ever in pursuit of vigor, variety, elasticity, mutation of movement, and potency of patter. A music, that is, inclined to infinite plasticity.” A few pages later:

The development of the improvising rhythm section separates jazz from both African and European music, because the form demands that the players individually interpret the harmony, the beat, and the timbre while responding to one another and the featured improviser. To play such music demands superfast hearing — a component of genius that is one of the greatest stands against the mechanization of pop music, in which the players send in their parts to be mixed by producers and engineers.

Signs of the Times

Throughout the book you will find excoriating looks at U.S. history, with discerning views about pioneer filmmaker D.W. Griffith, boxing champions Joe Louis and Jack Johnson, Duke Ellington in Harlem, and many other aspects of society that shaped Parker’s world and thus the man himself. (And the rest of America, too, come to think of it.)

For example, in discussing one particularly offensive Cotton Club skit, Crouch brings two eras together: “It was a place where white customers could experience so-called ‘jungle nights’ in Harlem, full of what they thought to be the darkies’ ‘natural’ behavior — authentically imbecilic, if not amusingly or intriguingly subhuman, much like the thug-and-slut hip-hop world of today.”

Thanks to Crouch, we learn that the education of Charles Christopher Parker was a bit worldlier than yours or mine:

The shows, also known to the musicians as “smokers,” generally involved sex acts presented in an almost vaudeville style, with the band performing musical backgrounds for different kinds of erotic exhibitions. Men in dresses were seen performing oral sex on other men, or being mounted by men after being lubricated in a slow, sensual preamble. Women had sex with other women. Some puffed cigars with their vaginas; others had sex with animals. On those secret Saturday nights, playing third alto in Buster Smith’s band, sixteen-year-old Charlie Parker had his eyes opened yet further to the difference between what went on in the conventional world and what happened when people chose to reject the laws of polite society, to satiate their appetites, whatever they might be.

In weaving together race relations, American history, jazz, social mores, and Parker’s personal journey of discovery, Crouch has created a fascinating document, one that seems to exude a life force with every paragraph.

Riffing

In many passages, Crouch carries the reader along in a manner reminiscent of a Bird solo. Parker would first state (or flirt with) the melody, then create a counter melody, explore alternate chord progressions, and even indulge in some soaring riffs. In a similar fashion, Crouch begins a paragraph with a statement of meaning, enhances it with subordinate ideas, folds in an additional meaning, and creates a word-riff that can make reading each page a delightful shock.

It is a truly terrific book on its own, plus it has me eagerly looking forward to Part Two.

More information: http://harpercollins.com/books/Kansas-City-Lightning-Stanley-Crouch/?isbn=9780062005595 .

VIDEO: Stanley Crouch on jazz:

* * *

This original review is Copr. © 2014 by John Scott G and originally published on PublishersNewswire.com – a publication of Neotrope®. All commercial and reprint rights reserved. No fee or other consideration was paid to the reviewer, this site or its publisher by any third party for this unbiased article/review. Editorial illustration based on book jacket created by and © Christopher L. Simmons. Reproduction or republication in whole or in part without express permission is prohibited except under fair use provisions of international copyright law.